By the Aliyun conference of 2015, I saw a lot of news about docker. And it’s the third time of the year that I heard about docker.

I was lucky enough to have some quick conversations with the docker developers there, and I found that it’s really mature now. In fact, TaoBao also used docker for the internal deployment procedures, so I decided to try to move some projects of our company into the world of docker.

Introduction to Docker

Despite that the technology of docker itself is really mature now, it’s just too new that a lot of learning materials are just messy. And many items you found from Google are actually not consistent.

I would try to sort out those messy concepts (a little bit) here.

What is Docker

You may treat docker as some kinds of very light-weight virtual instances. It’s so light that, it even shares the same Linux kernel with the host machine.

This is an important thing to know, because it implies:

- Docker would work the best with Linux.*

- Inside the docker container, the kernel version must be the same as the one of host machine.

- Docker container is actually smaller than similar virtual instances (compared to VirtualBox and VMWare), because it saved the disk space for the Linux kernel.

- Docker used a lot of functionalities of Linux kernel (e.g. name space), so it only works with Linux kernel of version 3.10+.

- Docker boot is lightening fast, because you don’t need to load the kernel again. (See below for more details.)

- Actually docker could be installed on Windows and Mac. But in those cases, a mini-instance of VirtualBox Linux would also be installed so as to provide the required kernel.

Comparison of Docker with VirtualBox / VMWare

Similarities:

- Guest and host file systems are both separated. For example, command

ls /homeon docker container would have a different result than on the host machine. - Processes are separated. For example, ‘ps -a’ in the docker container would not show the processes of the host machine.

- Network interfaces and ports are bridged / tunneled from the host machine, just like VirutalBox or VMWare.

Limitations:

- You cannot get the UI from docker easily. Though there are some tricks to do that, the performance is not satisfactory in general.

- There is not actual boot process of the docker container, i.e. the

initprocesses ofssh,crontaband etc. are not automatically executed during the start of docker. - You can only run one persistent process inside one docker. You could, however, use some tricks like superevisord to start multiple a long-running process.

- You must use root permission to execute the docker related commands.

Advantages:

- Super light, a basic instance of Ubuntu may occupy about 100MB. The size is even smaller for Debian. It’s much smaller than the fresh installation of VirtualBox and VMWare.

- You could create images for docker containers very easily. The images are like the snapshots of VirtualBox/VMWare, except they are super light and super fast.

- You could push the docker images to docker repositories using git like tools. And you could pull them down from other machines right away.

- You could define configurations of docker (DockerFile) that would simply define steps to create a new image. That makes sharing of Linux environment much easier.

I believe the killer application of docker should be deployment. It basically wraps all configuration details into one image file, that could be pushed and pulled along different machines easily. So people do not need to setup the environment (and get stuck with compilation errors) again and again. My gut feeling is, docker would make Ubuntu even more popular than ever, the operating system is even more lightweight than before. People could create and destroy an OS configuration in a wink, just like software development debug cycles.

One example is the docker for Trac dev that I created weeks ago. It took me days to set up a full-blown development environment for the first time. But with this docker image, people could start development right way, and without needing to know about all the details of set up. (It took me quite a while to set up the multiple user configurations for the first time.)

Comparison with Virutalenv

Since I mainly used python (and Django) for the development, virtualenv is actually another ‘similar’ option for encapsulation.

However, the biggest problem with virtualenv is that it’s too high level (because the tool itself is python-based). Some libraries like lxml and PIL are just wrappers of C libraries, and hence they could not be embedded into the virtualenv environment.

Basic Usage

Here is a basic use case with docker:

- Install docker first.

sudo apt-get install docker.io - Pull a ubuntu image and run it.

docker run -i -t ubuntu:14.04This simple command would actually do all the following things:- download the image of ubuntu:14.04 from dockerhub (The default repository is fixed to dockerhub)

- run the docker image as docker container (see below for more explanations)

- assign a tty for the docker container:

-t - run the instance as interactive mode:

-i

- You could now play inside the docker container now.

- To leave the Docker, just press

Ctrl-C - To get back to the previous docker, however, you would need to find out the previous container process, and attach back

docker start <container id> - If you run the same command again, you would actually create a new container for the same image

docker run -i -t ubuntu:14.04

Docker Container and Docker Image

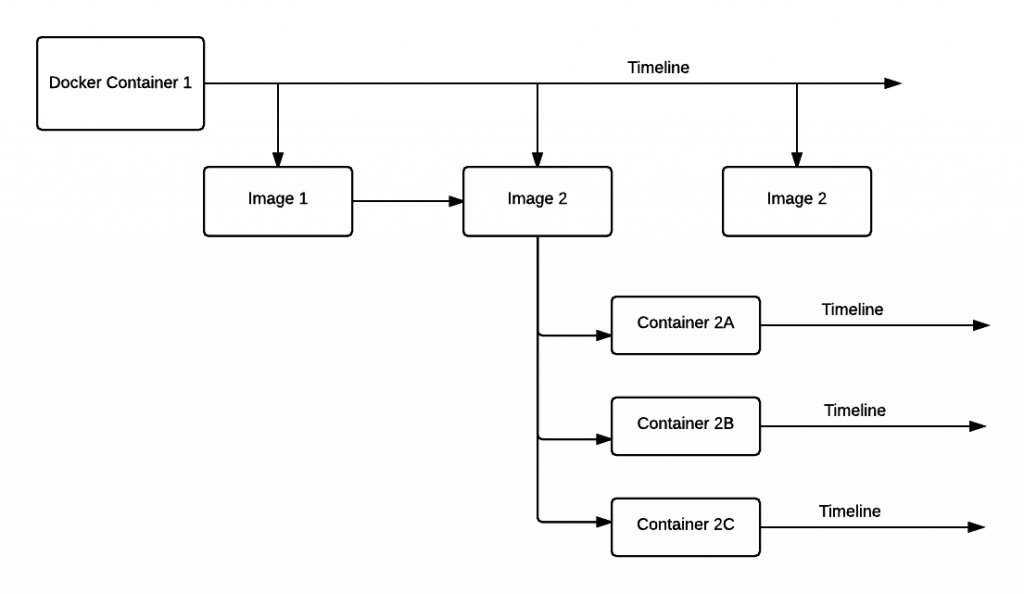

The relationship between container and image is a little bit like VirtualBox instance and snapshot. You could take snapshots for the VirtualBox instance at a different time. Similarly, you could make a snapshot for the container at a different time. However there is a subtle difference, you could also activate multiple dockers images of the container at the same time (to have multiple instances as a result), but you can hardly do that for VirtualBox.

So I guess a more accurate analogy would be git branch and tag. Each branch could be easily tagged, and each tag could introduce a new branch.

In many senses, the docker operations are similar to git. Here are some of them:

- To check all existing images:

docker images

- To check all activated docker containers:

docker ps

- To check all docker containers, including those exited:

docker ps -a

- To freeze the current status of container and make it a new image:

docker commit <container_id> <repository>- Note that the repository you committed to may not be the same as the one you pulled from. For example, you may pull ubuntu:14.04 from a public repository, and want to push to your own private repository.

How to transfer the Docker Image from one machine to another

The most important part of any virtual instance, is that it could be easily cloned and migrated. And it’s particularly easy for Docker.

Import and Export

This is the most raw way to clone out the image, and it has no dependency of any repository server.

- Export the image first

docker save ubuntu:14.04 > ubuntu14.04.tar

- Copy to another machine using ftp or rcp

- Import to the machine

docker import < ubuntu14.04.tar

Pull and Push

This is a more common practice:

- Apply account in DockerHub

- Create image for the current container:

docker commit <container_id>

- Find out the image id of the newly created image:

docker images

- Make a tag for the image, and specify your docker username in the new repository name

docker tag <image_id> walty8/ubuntu-test

- Push the tagged image

docker push walty8/ubuntu-test

Note that a free user could only host 1 private project on DockerHub. You have 3 options if you want to push images of more than one project: 1. Pay DockerHub for more private project slots 2. Open source your projects, and make them public. Docker hub has no limitation on the public projects. 3. Set up your own private repository.

I should talk more about the set up of a private repository, DockerFile and docker compose in a separate blog post.